Trying to Define My Astrological Practice

Recently, I obtained an opportunity to teach a 101 class on astrology in the summer at a local metaphysical store. I'm also potentially going to start selling short, sweet natal readings at a local pagan pop up. Not one to half ass anything, this is forcing me to confront something that has dogged me for awhile: what is my personal style of astrology?

The predominant approach to astrology among today's most prolific astrologers—including Chani, who you may know from her podcast and app—is Hellenistic astrology. Most astrologers who practice this form of astrology were taught by Chris Brennan, who brought this set of historical methods into modern prominence with his book Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune and his podcast The Astrology Podcast. Brennan and his fellows often call themselves "traditional western" astrologers. But there are a couple of issues with what we call traditional western astrology.

Traditional western astrology is not "traditional" as in coming from an unbroken line of teacher to student, but "traditional" as in recovered from ancient texts. These texts are survivors from eras—Mesopotamian, Hellenistic, Roman, Islamicate, Medieval—whose material have been largely lost to time. Very few ancient practitioners' texts have made it into our hands and out of those, bibliographies are incomplete. So when someone practices a form of traditional astrology, they're actually practicing a few techniques that we have access to, whereas there was likely a lot more diversity to what was actually practiced over 1000s of years.

The second issue is, because Uranus and Neptune were only discovered in 1781 and 1846 respectively, they are not practiced in forms of astrology prior to that time as they are not visible in Earth's sky. However, modern astrology assigns meaning to them and utilizes them in readings. Brennan, and many of his cohort, do as well. I will say from personal experience that Uranus and Neptune are quite loud and very much do play a part in at least transits, so the usage of them is more than fair. However, they do not fit in the majority of traditional techniques because Hellenistic astrology has a very specific cosmology and theology revolving around the 7 traditional planets. This leaves the three "outers," including Pluto, as extant and there are ongoing discussions about how to incorporate them.

What I am trying to determine is how I rationalize such idiosyncrasies. I also find myself caught in the middle of two belief systems: I am a planetary polytheist who worships the planets under their mostly Roman names, but I am also a descendant of Mesopotamians, the people who started western astrology. How much of my heritage, as far away as it is, is applicable to today's astrologer?

Mesopotamia existed for 3000 years and had several recorded forms of astrology in the source fragments we have recovered. Mesopotamian astrology began as purely mundane and in regards to portending omens from the night sky as to what future events would befall the kingdom/society. One such omen from Gavin White's Babylonian Star-lore contains the usual formula, in this case inferring that Mars was traveling through the constellation of Scorpio:

If the Scorpion sets dull-lighted: the food of men will become poor.

According to Ulla Susanne Koch in Mesopotamian Astrology, the planets and stars were initially seen as the literal gods that bore their names sending messages to the kingdoms:

The stars and planets were celestial manifestations of gods but also seemed to be gods in their own right... Sometimes evil omens were seen as an expression of anger [...] so that particular god had to be appeased. In this way, messages can be sent directly from a god to a king.

Later on, in the Persian and Seleucid periods, the structure of astrology became more familiar to what we see today. The zodiac became no longer about the constellations but were split evenly across the sky. Natal astrology was developed. The Egyptian terms, still in use today, are thought to have Mesopotamian roots. So does most of Mesopotamia's exaltation system to the Hellenistic conception of essential dignity with the exception of Venus' "secret exaltation"* in Leo.

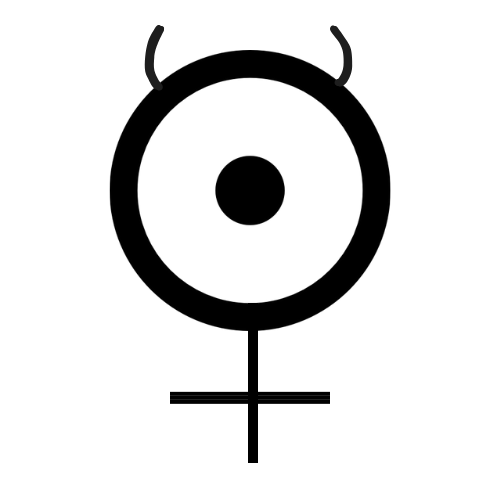

It is the exaltation system—later expanded by Hellenistic astrology with domiciles, depressions (or falls), and detriments—which perhaps shows the deepest split between cultural conceptions of the planets. The biggest differences occur in relation to Venus and Saturn.

In Mesopotamia, Venus is Inanna who exalts in both Pisces and Leo. The latter was common sense because her animal was the lion and Leo is the constellation/sign of the lion. Persian astrologers, particularly Mashallah who lived in formerly-Mesopotamia then-Persia from 740 to 815, noted that natives with Venus in Leo are "able to achieve most all visions which they hold in their heart." This is a very Inanna-esque description, 100s of years after she was worshipped in the region. However, in Hellenistic astrology, Venus is a cold, moist planet who is peregrine in hot, drying Sun-ruled Leo. This means that she holds no special power in Leo on her own.

In addition, in Hellenistic astrology, Venus rules over Libra and Taurus according to the Thema Mundi due to not ever being more than two signs away from the Sun. Libra, notably, is Saturn's sign of exaltation in the Mesopotamian tradition. This is because Libra was originally the Scorpion's Claws and then later became The Scales, thus starting with pain and then developing into justice. This gives Saturn important associations with pain and justice, particularly judicial sentencing or more broadly consequences. Some sources suggest that Saturn and the Sun were seen as the same body with Saturn standing in for the Sun at night, both of them favored toward justice for the kingdom. This meant the Sun was considered well-conditioned in Libra in Mesopotamian astrology while in Hellenistic astrology he is seen as in his fall.

In further contrast, later Hellenistic astrology sees the Sun and Saturn as enemies. As part of this, Saturn rules Capricorn and Aquarius with the latter opposing the Sun's sign of Leo. Aquarius is, to put it crudely, a weird fucking sign when tracked throughout history. When ruled by Saturn in Hellenistic astrology, it is fixed, cold, representative of deconstruction at best and destruction at worst, which is consistent into later forms of traditional astrology. In Mesopotamia, Aquarius was the constellation/sign of Gula, a proto-Hekate magician healer goddess, and therefore particularly community-oriented in a cultural framework that is already much more community-oriented than my own American individualistic society. In modern pop astrology, a conception I don't agree with but think is worth noting, Aquarius is ruled by Uranus and defined by progressive revolution.

Both the most ancient form of astrology and the newest agree: Aquarius is a humane sign. From my observations, those with Aquarius Suns or strong Aquarius placements such as stelliums or Ascendants, are people-centered and tend to have very structural viewpoints while often having aloof demeanors per the Hellenistic descriptions. This is arguably also a Gula-esque description.

But I don't worship Gula. And my time with Inanna concluded a few months after I started my gender transition. So... where does that leave me?

I understand that I am not going to be a Mesopotamian astrologer because too little has survived for helpful reconstruction. I also don't want to be a Hellenistic astrologer because it doesn't make any sense to me to go so far back in history to a time and culture of which I have little personal connection. Additionally, later forms of traditional astrology such as Islamicate and Medieval syncretized Hellenistic methods with others and invented new ones. Islamicate still holds appeal because it does contain traces of Mesopotamian perspective on astrology. However, I found my one Islamicate-styled reading from a professional astrologer unenthralling and not as detailed as was promoted.

So I guess I'll just read some more. Right now, some academic books on western astrology throughout history. Later, maybe more Ben Dykes translations of the Persian astrologers. But I suspect I'll never have a complete answer about my astrological approach. It'll keep growing and changing as I learn and observe, as mutable and liminal as the rest of my practice.

*"Secret exaltation" is probably not so secret. White uses this phrasing for Venus in Leo, but Brennan notes that the exaltations in general seem to be associated with what in cuneiform texts is called bit nisitri "secret houses" or asar nisirti "secret places."