Decolonizing Notions of Language and Rethinking Verbs (Through Herbalism?)

The first thing my herbalism teacher had us do before our first class this past Sunday was listen to this podcast Ego to Eco Identity by Tara Brach. I am not mentioning this podcast to recommend it; I thought it was disorganized and rambling as the least offensive of its crimes. More pertinently, Brach self-identifies as a Jungian, a class of thinkers I harbor deep skepticism toward because—very much like their founder Carl Jung, who has several original ideas I appreciate despite his racism—they tend to have a very flexible-to-the-point-of-fictional idea of history. However, I am bringing this podcast up because in our actual class, someone said they loved the "fact" mentioned that "Indigenous languages are about 75% verbs and 25% nouns compared to English which is 75% nouns and 25% verbs."*

Brach did not source where she got this idea from and the only place I have seen it repeated is the website for the UK-based organization Festival of Debate, which also does not provide a source and notably has nothing to do with American indigenous tribes. First, when you see a breakdown as clean as 75/25%, that is your first hint that it is inaccurate because statements with data numbers draw attention more than statements without them, which fuels their spread. Other websites, such as one that is for a Minnesota-based Native American language nonprofit, make the same assertion without this quantitative breakdown.

But the first reason I smelled that there might be something off about this statement is because I studied Victorian literature in undergrad, which is the era where white people started romanticizing Native peoples and their supposed ultra special connection to nature ala Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimoore Cooper. Basically, the 1800s was around the time Americans started feeling very comfortable that they had secured the so-called United States from the hundreds of Native populations they had worked hard to eradicate or move off their land. The attitude toward Native peoples thus evolved from viewing them as an immediate danger to seeing them as mystical and wise, like an indigenous version of the Magical Negro trope. Meanwhile, indigenous children were still being separated from their families to forcibly attend boarding schools to Christianize and whitewash them.

Maybe the verb-favored ratio is true of Anishinaabemowin since the Festival of Debate's website directly uses that language as an example, but something being true of one tribe does not mean it is applicable to all Native American tribes. As Native American advocacy/thought will tell you, the only thing that truly connects indigenous people as Native American is that their ancestors were on the land prior to European colonization and that they experience ongoing marginalization that has resulted from it (source: A Native American Encyclopedia by Barry M. Pritzker, which I read in 2017).

Indigenous languages do, in fact, challenge typical linguistic assumptions about how languages develop. However, throughout the 500+ tribes that lived throughout the "United States," these languages were so numerous and diverse they belong to 9 separate language families. So in addition to my failure to find sources for the claims made by Brach and others, it's doubtful that all indigenous languages are similar enough to make generalizations about their constitutions. To do so is a continuation of the colonialist perspective of viewing all those tribes as a monolith instead of as many different cultures with their own unique languages, traditions, spiritualities, and nuances.

I am particularly sensitive to this issue because when I embarked on learning more about herbalism, I wanted to do so with the goal of establishing a respectful relationship with the land I moved to two years ago. This land—like the Lenape land I was born and raised on—is stolen. By moving within the colonialist system that is the US freely, I partook in that ongoing theft. I can't ethically practice a local herbalism without keeping that fact in mind as it is inherently tied to sustainable herbal practices that avoid further exploitation of the land (for instance: the local tribe in my area is one of those to use white sage, which is threatened by harmful harvesting practices perpetuated by outsiders, in ceremonial settings).

This is not to lambast my herbalism teacher, who is part Hawaiian and comes from the Western herbalism tradition, for assigning Brach to us. It's simply that I could not hear this podcast without soundly criticizing and rejecting it for its mindless contributions to racism and objectification of indigenous people.

***

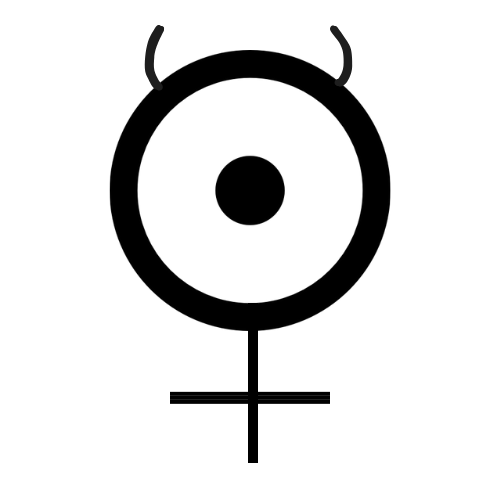

Yet, there is something intriguing about putting more emphasis on verbs over nouns as a genderqueer person.

Testosterone has begun changing my face and I am starting to look more like my brother. At this point, I am getting categorized as a "woman" or a "she/her" more because of the roundness of my chest than anything else. Truly, it is unclear to us who belong to neither side of the binary how others decide what a man or a woman is with how inconsistent the signs are.

What I verb matters. The "menswear" I put on daily. The dropping of my voice and the way I intentionally augment my vowels so that they read as more masculine. The pronouns I use. Everything I do matters more than what my body is.

So there is a temptation toward experimenting in using more verbs when discussing bigger ideas. Not because I need to idealize and appropriate real or imagined indigenousness. Not because verbs increase connectivity, a claim so broad as to have neutral moral value** if true. But because in English doing so forces us to get more specific when communicating to each other. What does decolonization mean? What actions do we see in order to achieve it? What attitudes must we deconstruct? What does our personal activism include?

*As my friend Valentine pointed out, there is also more to language than just nouns and verbs so whoever made this up to a perfect 100 percentage also knows less about language than a kindergartener

**Again, I can't say I know anything about Anishinaabemowin, but the Navajo/Diné language inherently has a person>animate creature>inanimate object hierarchy that balks against the stereotype of Natives as nature-loving equalizers. In Diné, an animal is seen as not having the same amount of agency as a person. So, for example, a horse cannot kick a human. The human can only be kicked by the horse. Verbs as they work in English are not universal; they depend on a language's larger construction, which is in turn based in cultural perspective, in order to deliver function